The Abbasid Empire

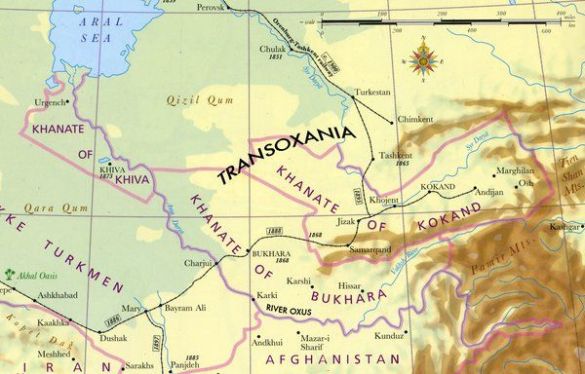

The Abbasid empire, at its zenith in the 9th century AD, stretched from the environs of Constantinople and Egypt to Central Asia and the Arabian Peninsula. Their expansion efforts were initially focussed more towards Central Asia in fighting the nomadic pagan Turks, rather than making a serious bid for the conquest of India. By the end of the 9th century, however, the empire started disintegrating and a series of aggressive, expansionist states arose that had all accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Caliph who legitimised their position by granting them a formal letter or manshur. The rulers of these states were called ‘Sultans‘ and most of them were Turks. These Turks originated in the areas that we now know as Mongolistan and Sinkiang and had, over the course of a couple of centuries, infiltrated the region called Māwarā’ al-Nahr or Transoxiana (the transitional zone between Central Asia and West Asia). The Iranian rulers of the area, and the Abbasid Caliphs, brought in further more Islamized Turks as mercenaries and slaves and employed them as guards and military personnels. They were gradually assimilated into the Persian culture that was quite dominant in the region during this era.

The Samanid Empire

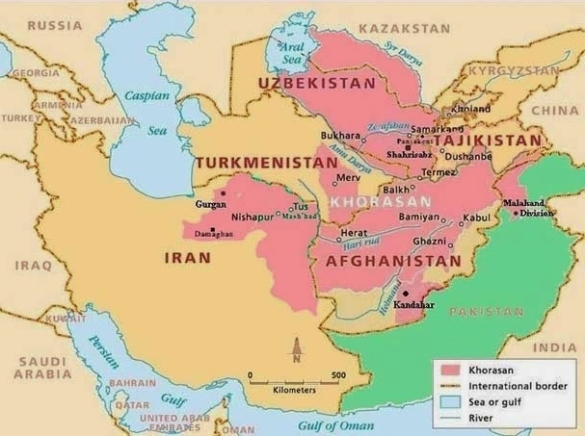

One of the most powerful dynasty that arose in the region during the late 9th century was of the Samanids (820-999) who had their capital initially at Samarkand and later on at Bukhara. The Samanid Empire, a Sunni Iranian empire, was founded by four brothers – Nuh, Ahmad, Yahya and Ilyas – who were each gifted the governorship of Samarkand, Farghana, Shash (Tashkent), and Herat, respectively, by the governor of Khorasan in return for their aid to the Abbasid Caliphate against fighting the rebels of the area. In 892 AD all the four states were united into one by Ismail I, the son of Ahmad, and the empire thus became mostly centred in Khorasan and Transoxiana, with Bukhara as the capital. At its greatest extent, it encompassed all of today’s Afghanistan, and large parts of Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Pakistan. It derives its name from the eponymous ancestor of the Samanid Dynasty, Saman Khuda (originally a Zoroastrian who later converted to Islam), a Persian noble who belonged to a dehqan family, which was a class of landowning magnates, who could trace their descent back to the Sasanian era. The Samanids promoted arts, giving rise to the advancement of science and literature, and thus attracted scholars such as Rudaki (poet), Ferdowsi (poet) and Avicenna (philosopher and chemist). While under Samanid control, Bukhara was a rival to Baghdad in its glory. The period saw the creation of a Persianate culture and identity that brought Iranian speech and traditions into the fold of the Islamic world. One of the most significant contribution of the Samanid age to Islamic art is the pottery produced at Nishapur and Samarkand. The Samanids developed a technique known as slip painting: mixing semifluid clay (slip) with their colours to prevent the design from running when fired with the thin fluid glazes used at that time. The potters employed Sasanian motifs such as horsemen, birds, lions, and bulls’ heads, as well as Arabic calligraphic design. From the mid-10th century, Samanid power was gradually undermined, economically by the interruption of the northern trade and politically by the internal power struggles. Weakened, the Samanids became vulnerable to pressure from the rising Turkish powers in Central Asia and Afghanistan.

The Ghaznavid Empire

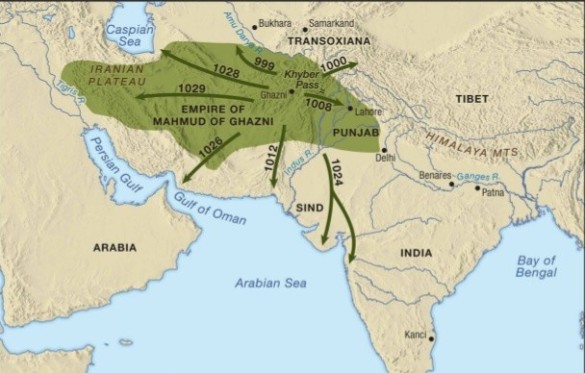

Another such empire that sprung in the mid-10th century was of the Ghaznavids (962-1186 AD). One of the last Samanid amirs, Nuh II, to retain at least nominal control, confirmed Sebuktigin, a former Turkish slave, as semi-independent ruler of Ghazna (modern Ghazni, Afghanistan) and appointed his son Mahmud governor of Khorasan. But the Turkish Qarakhanids, who then occupied the greater part of Transoxania, allied with Mahmud and deposed the Samanian Mansur II, taking possession of Khorasan. Bukhara fell in 999 AD, and the last Samanid, Ismail II, after a 5 year long struggle against Mahmud of Ghazni and the Qarakhanids, was assassinated in 1005 AD. The Samanid domains were split up between the Ghaznavids, who gained Khorasan and Afghanistan, and the Qarakhanids, who received Transoxania; the Oxus river (Amu Darya) thus became the boundary between the two empires. Ghaznavid power reached its zenith during Mahmud’s reign who created an empire that stretched from the Oxus to the Indus valley and the Indian Ocean; in the west he captured (from the Buyids – an Iranian Shia dynasty) the Iranian cities of Rayy and Hamadan. A devout muslim, Mahmud reshaped the Ghaznavids from their pagan Turkic origins into an Islamic dynasty and expanded the frontiers of Islam. The Persian poet Ferdowsi (died around 1020 AD) completed his epic Shahnameh (‘Book of Kings’), a poem of nearly 60,000 couplets, at the court of Mahmud in about 1010 AD. The Shahnameh was for the most part the translation of a Pahlavi (Middle Persian) work, the Khvatay-namak, a history of the kings of Persia from mythical times down to the reign of Khosrow II (590-628), but it also contained additional material continuing the story to the overthrow of the Sasanians by the Arabs in the mid-7th century.

However, after his death, Ghaznavid power was challenged by the Seljuq Turks and in 1040 AD, after the defeat in the Battle of Dandanqan, the Ghaznavids lost all their territories in Iran and Central Asia to the Seljuqs. The Ghaznavids were left in possession of eastern Afghanistan and parts of northern India (now Pakistan) where they continued to rule until 1186, when Lahore fell to the Ghurids (a dynasty of Eastern Iranian descent from the Ghor region of present-day central Afghanistan).

Meanwhile, during this time-span of about a century the Qarakhanids had been converted to Islam. Early in the 11th century the unity of the Qarakhanid dynasty had already been fractured by constant warfare. At the end of the 11th century, they were forced to accept Seljuq suzerainty. With a decline in Seljuq power, the Qarakhanids in 1140 fell under the domination of the rival Turkic Kara Kitai confederation, centred in northern China. Uthmān (reigned 1204-1211) briefly re-established the independence of the dynasty, but in 1211 the Qarakhanids were defeated by the Khwarezm Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad and the dynasty was extinguished. This newly established Khwarezmid empire had its capital at Merv. It was destroyed, in the 13th century, by the Mongol, Genghis Khan.

Khwarezmian Empire

In the fierce battle for survival in West and Central Asia, military efficiency was considered the most valuable asset and it was precisely this factor which led to the growth of militarism that spelt immediate danger to India and its outlying area – Zabulistan and Afghanistan which till, then, had not been converted to Islam.

More in the last part i.e. Part 3

Your blog never ceases to amaze me, it is very well written and organized.;-:~.

LikeLike